La ricetta per il perfetto astrofilo: oscurità, pazienza e predisposizione ad accettare che là fuori possa esistere tutto ciò che immaginiamo.

E bisogna anche avere una buona dose di elasticità mentale ad immaginare lo spazio infinito, quell’ultima frontiera che apre mondi senza fine.

«Quando guardi le stelle, guardi indietro nel tempo» mi accoglie così Carlo Margaro, astrofotografo per passione che, assieme al suo compianto fratello Mauro, ha scattato fotografie alla volta celeste apprezzate sia dalla NASA che dall’ESA, oltre ad aver ricevuto i complimenti della Professoressa Hack.

Assieme a lui ci sono l’astronomo e divulgatore scientifico il Professor Walter Ferreri e il Presidente degli APA, gli Amici del Polo Astronomico, Daniele Corna.

Ci troviamo ad Alpette (957 m s.l.m.) definito dagli anni ‘80 il “Paese delle Stelle” grazie al lavoro di Don Giovanni Capace: appassionato e studioso di astronomia, verso la fine degli anni ‘70 decide di installare un potente telescopio Newton nella canonica, permettendo ai parrocchiani e ai visitatori di sollevare lo sguardo a rimirar le stelle.

Prima di passare a miglior vita, il parroco dona il telescopio al comune che decide di costruire al di sopra dei propri uffici la cupola dell’osservatorio e spostare al suo interno il lascito del Don.

Verso la fine del secolo scorso, il Newton diventa obsoleto e viene sostituito con un Ritchey-Chretien più grande, con la conseguente ristrutturazione e meccanizzazione della cupola che raggiunge i 5,5 metri di diametro. Il nuovo telescopio, dell’azienda italiana Macron, ha un riflettore di 60 cm di diametro (il più grande su suolo italiano è di 180 cm): «con dimensioni del genere si possono già fare dei lavori professionali, di ricerca – spiega il Professor Ferreri – e grazie alla lunga focale, ovvero la distanza tra lo specchio e dove si forma l’immagine, si possono vedere milioni di astri e fotografare anche i più deboli; si può vedere perfino Plutone». Questo strumento è accoppiato ad uno più piccolo di 12 cm di diametro, che permette l’osservazione quando la turbolenza dell’aria è troppo eccessiva per il Ritchey.

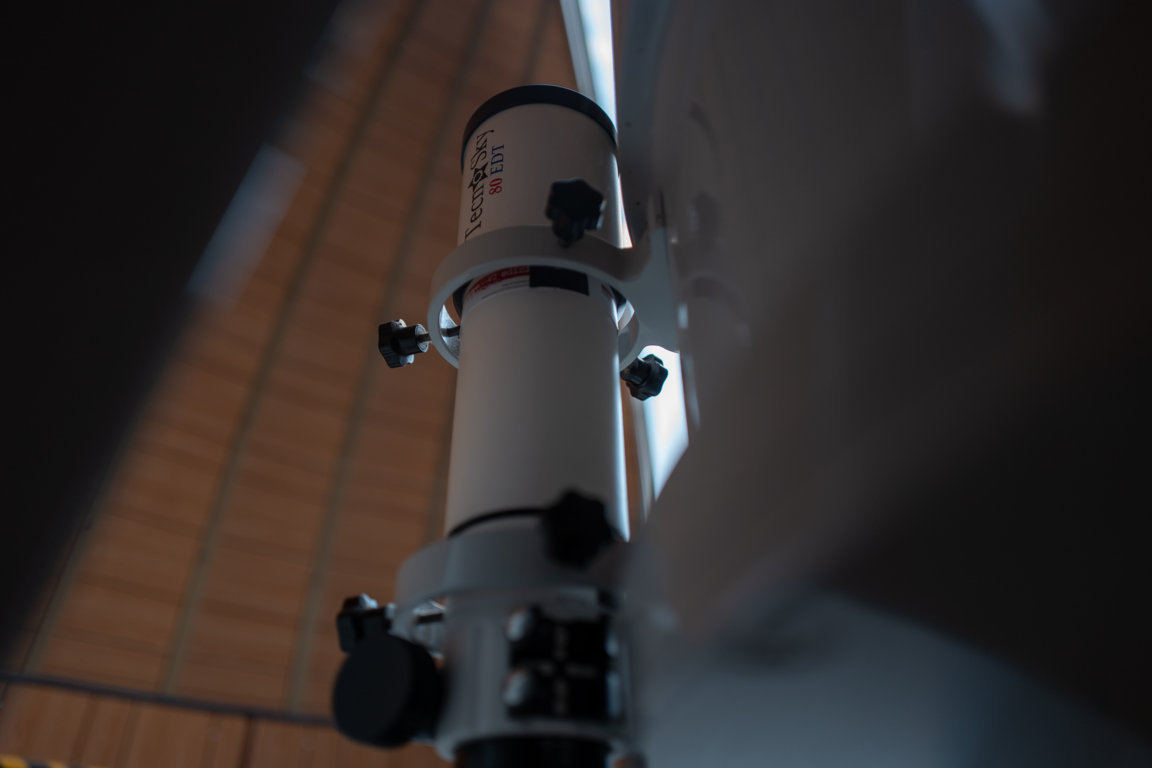

A completare il terzetto c’è l’ottantino, che essendo molto piccolo, permette di fotografare una porzione di cielo molto più ampia e vedere nella sua interezza la Luna, un campo stellare o una cometa con una coda molto lunga.

Nel 2010 è stato affiancato all’osservatorio il planetario con una capienza di 54 persone, per osservare la volta sia di notte che di giorno con qualsiasi condizione atmosferica.

«L’associazione è nata dopo la costruzione del planetario», mi spiega il Presidente «prima il polo era gestito da un’altra associazione che ha fatto un ottimo lavoro di gestione e mantenimento, ma noi volevamo fare le cose in modo diverso, aprendo a tutti (studenti e non) la possibilità di osservare e studiare il cielo».

Quando è subentrata l’APA, è stato invitato a partecipare il Professor Ferreri che già era di casa ed era allora responsabile delle relazione pubbliche dell’Osservatorio di Pino Torinese, gestito da INAF (Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica). L’esperto di asteroidi è stato poi affiancato dai gemelli Margaro, diventati poi soci onorari del polo. Il gruppo ha partecipato e partecipa tuttora agli eventi di divulgazione scientifica organizzati dall’associazione, agli “Star Party” e alle visite guidate. Questi eventi rappresentano i motivi per cui nel 2018 Alpette ha ricevuto la Certificazione Herity International dell’Organismo Internazionale per la gestione di qualità del Patrimonio Culturale.

«Fotografare il cielo non è semplice, non basta un clic» mi dice Margaro. Pazienza, appunto, e tanta tenacia, come quella volta che lui e Daniele Corna hanno passato la notte a Ribordone per fotografare una cometa, a -10°.

Tuttavia, la difficoltà più grande non è trovare l’oggetto, ma inseguirlo: in un’ora si percorrono 15 gradi per via della rotazione terrestre, perciò bisogna seguire bene ciò che si vuole fotografare per evitare di ottenere una foto mossa; l’inseguimento avviene tramite una guida fuori asse e lavorando su due telescopi, di cui uno guida l’altro.

«Io ho sempre fatto il fotografo, assieme a mio fratello. Un nostro amico appassionato di cielo e stelle veniva spesso nel nostro studio a Ivrea dicendoci che avremmo dovuto iniziare a sollevare gli obiettivi verso l’alto. Una cosa mi rimase impressa: ci spiegò che se si guarda il cielo e tra le stelle che brillano se ne vede una che non brilla, quella è un pianeta; una notte non riuscivo a dormire e, dopo aver montato un piccolo telescopio che ci avevano regalato per Natale, l’ho puntato verso una di quelle “stelle che non brillano”. Mi sono spaventato: era Saturno». Il resto è una storia che dura da più di 20 anni, milioni di stelle viste e diverse centinaia di chilometri percorsi nel mondo, alla ricerca dei cieli più belli.

Passare dalla mera osservazione all’astrofotografia non è così semplice: «Con il telescopio vedi soltanto lo 0,1% di quello che vedi in fotografia: solo con essa puoi vedere, ad esempio, le nebulose, le sabbie del tempo».

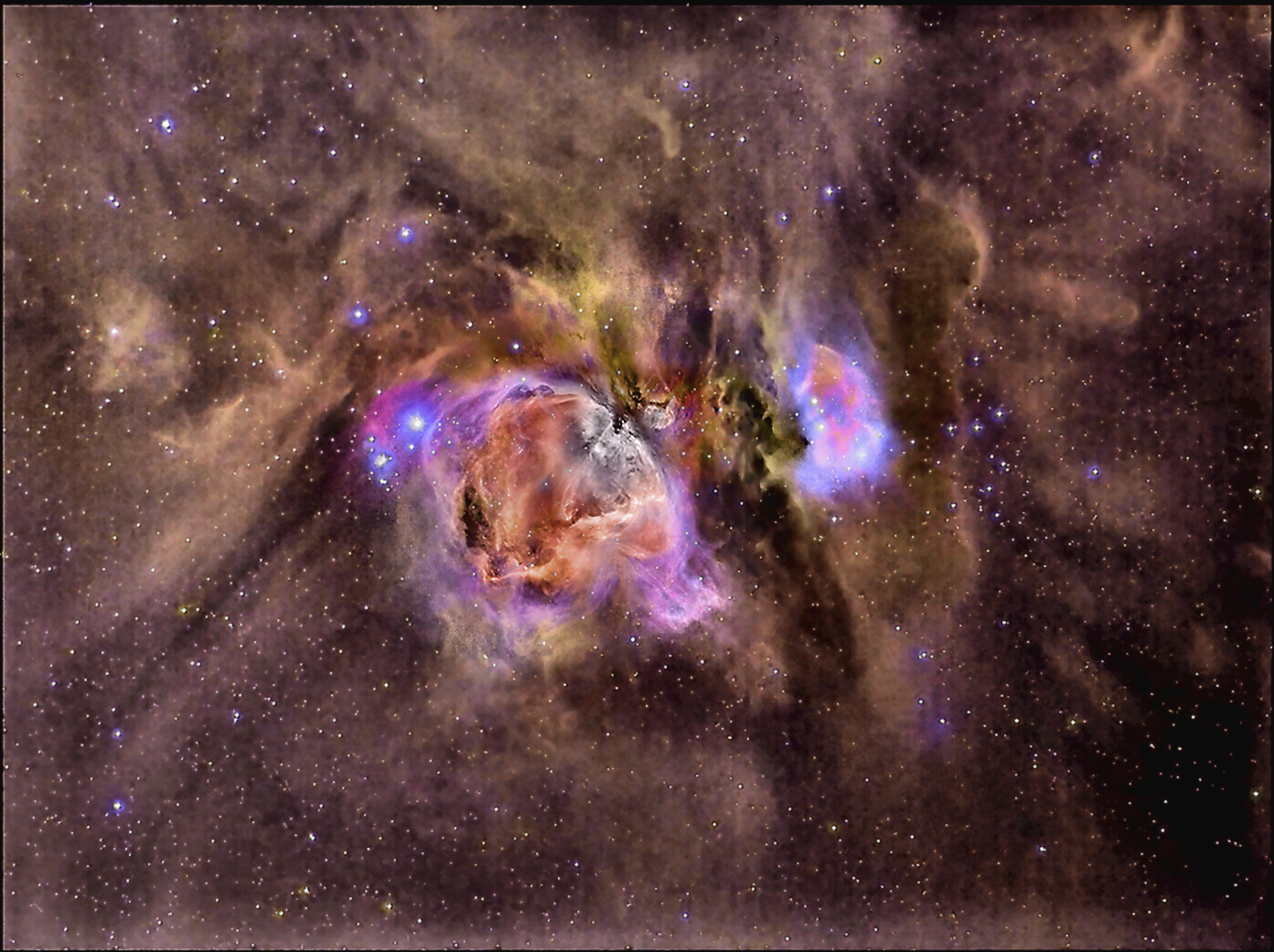

Dopo anni di osservazione i Margaro si sono detti: “Siamo fotografi, possibile che non ci sia un modo di fotografare il cielo?” Apparecchi via via sempre più sofisticati, nonché il passaggio dall’analogico al digitale, gli hanno permesso di vedere ciò che prima gli sfuggiva. Con l’utilizzo di filtri colorati (RGB, rosso-verde-blu), infine, si ottengono gli scatti che vedete in queste pagine: sovrapponendo le foto ottenute con i filtri a quelle acromatiche che danno la luminanza si ottiene la foto a colori dell’oggetto. Un procedimento complicato, quindi, ma direi che il gioco vale la candela.

Dopo alcune disquisizione su asteroidi ipoteticamente letali, viaggi su Marte e alieni, nonché un invito a fotografare gli astri, il Presidente, il Professore e l’astrofotografo mi hanno dedicato una sessione nel planetario con un assaggio di ciò che propongono al pubblico: tra stelle, pianeti, costellazioni e galassie, il cielo, quella sera, era tutto per me.

www.osservatorioalpette.it

Astrofoto Fratelli Margaro

Village of Stars

The Alpette Enterprise

The makings of an ideal amateur astronomer: obscurity, patience and a willingness to accept that out there, anything you could ever dream up might exist.

They also need a hearty dash of open-mindedness to be able to imagine infinite space, the final frontier leading to infinite worlds.

«When you’re looking at the stars, you’re looking back in time». That’s how Carlo Margaro greets me, a passionate astrophotographer who, alongside his late brother Mauro, snapped shots of the celestial sphere admired by NASA and ESA alike, as well as being complimented by Italy’s celebrated Professor Margherita Hack.

Next to him, there’s popular science writer and astronomer Professor Walter Ferreri and Chairman of the APA, Amici del Polo Astronomico (Friends of the Astronomy Hub), Daniele Corna.

We’re in Alpette (957m AMSL), described in the ‘80s as the “Village of Stars” thanks to the work of Don Giovanni Capace, parish priest and astronomy scholar and enthusiast. Toward the end of the ‘70s, he decided to install a powerful Newton telescope in the rectory, allowing parishioners and visitors to lift their gaze and wonder at the stars.

Before passing away, the priest donated the telescope to the town council, which decided to build an observatory dome right above their offices and relocate Don Capace’s legacy to within it.

The Newton became obsolete toward the end of the last century and was replaced by the larger Ritchey-Chretien with subsequent refurbishing and mechanizing of the dome, which spans 5.5 m in diameter. The new telescope, from the Italian company Macron, has a 60cm diameter reflector, the largest in Italy being 180cm: «Using these magnitudes, you can carry out professional work and research», explains Professor Ferreri, «and thanks to its long focal length, meaning the distance between the mirror and where the image forms, you can see millions of celestial bodies and take photos of even the faintest ones. You can even see Pluto». This piece of equipment is coupled with a smaller 12 cm diameter one, which allows for observation when there is too much atmospheric turbulence for the Ritchey.

To make it a trio, there’s the Ottantino. Being rather small, it allows for photographing a much wider section of the sky and seeing the moon, a field of stars or a long-tailed comet in its entirety.

In 2010, a 54-person capacity planetarium was joined to the observatory for observing the cosmos whether it’s night or day, and in any atmospheric conditions.

«The association was founded after the planetarium was built,» the chairman tells me, «the Astronomy Hub was previously managed by another association, who maintained and managed it well, but we wanted to do things differently. I guide everyone (students and non-students) in how to observe and study the night sky».

When the APA stepped in, Professor Ferreri was invited to get involved, who already felt at home and was then PR director for the Pino Torinese Observatory, managed by INAF (National Institute of Astrophysics). The asteroid expert was later joined by the Margaro twins, who then became honorary members of the Astronomy Hub. The group was, and still is, involved in public engagement with the association organizing science events from “Star Parties” to guided tours. These events are why, in 2018, Alpette received the Herity International Certificate from the International Body for Quality Management of Cultural Heritage.

«Taking photos of the night sky isn’t easy, you can’t just snap a quick shot», Margaro tells me. It requires patience and a great deal of determination, like that time when he and Daniele Corna spent the night in Ribordone to take a photograph of a comet, in -10°.

Yet, the greatest challenge isn’t finding your subject, it’s tracking it. Due to the earth’s rotation, it can move up to 15 degrees in one hour, which means you need to follow what you’re photographing closely so you don’t get a blurry photo. Tracking is aided by a short off-axis guider and by working on two telescopes, one guiding the other.

«I’ve always been a photographer, so has my brother. One of our friends, a star and sky enthusiast, used to frequently visit our Ivrea studio saying that we should set our sights higher. One thing really stuck with me: he told us that if you look at the night sky, among those twinkling stars you’ll see one that’s not twinkling. That’s a planet. So one night when I couldn’t sleep, after mounting a small telescope they gave me for Christmas, I pointed it at one of those “non-twinkling stars”. I was astounded: it was Saturn». The rest is a story that goes on for over 20 years, with millions of stars seen and several hundreds of kilometers traveled across the world, in search of the most beautiful skies.

Going from mere stargazing to astrophotography isn’t that simple: «With a telescope, you only see 0.1% of what you see in a photo. Only through photos can you see, for instance, the nebulae. The sands of time».

After years of star gazing, the Margaro brothers asked themselves: “We’re photographers, could it be that there’s no way to photograph the sky?” Little by little, with increasingly sophisticated tools together with the transition from analog to digital, they were able to see what initially evaded them. By using colored filters (RGB, red-green-blue), they eventually got the photos you see on these pages. By overlaying the filtered photos with the bright colorless ones, they get a photo with the object’s true color. So it’s a complex procedure, but I would say it’s well worth the effort.

After some in-depth discussions on hypothetically life-threatening asteroids, journeys to Mars and aliens, as well as an invitation to take photos of celestial bodies, the Chairman, Professor and astrophotographer offer me a planetarium session with a taster of what they offer the public. Stars, planets, constellations and galaxies. That night, the sky was all for me.

www.osservatorioalpette.it

CREDITS

Foto di copertina Alessandro Aimonetto

Articolo di Linda Zucca Bernardo